South Africa’s GDP contracted by 1.3% in the fourth quarter of 2022, according to the latest Stats SA report. This is bleak news, but a look at Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) data from the same report exposes something deeper, and arguably more interesting, than the GDP snapshot.

GFCF is a measurement of real new investments, which does not include shifts in inventory, or paper-thin bets on stock markets. Think instead of building factories and offices, or buying machines and equipment. GFCF is arguably the most reliable lead indicator of future economic performance because today’s investments co-generate tomorrow’s product.

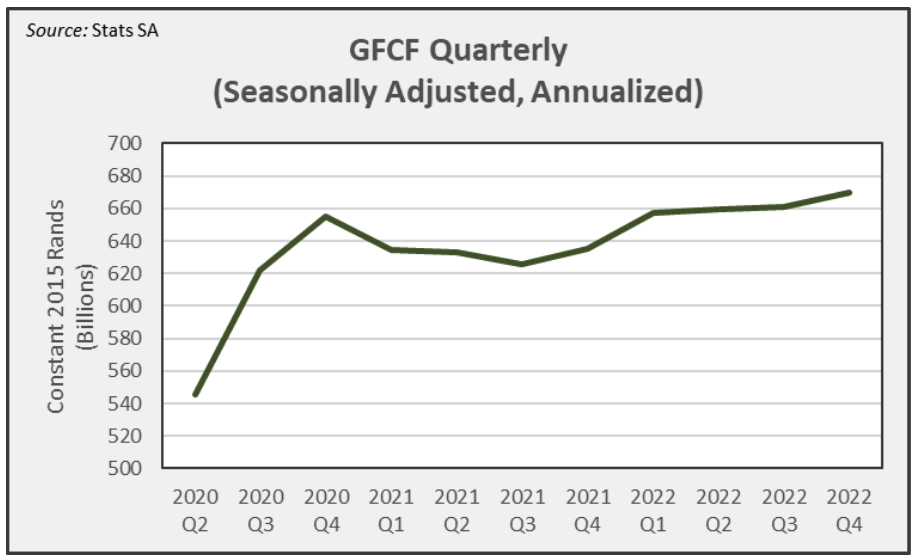

So what is GFCF data telling us? There was a year-on-year increase of 4.7% in 2022. Even more impressively, there has been a 22.8% increase in GFCF since the low point of Q2:2020.

This looks so good one could even call it investment’s “new dawn”. President Cyril Ramaphosa is weathering bad news cycles, so that phrase is out of fashion, but evidence matters, and the graph above paints a nice picture of capital rising.

To be fair, it is not all good news. Most of the “new dawn” happened in 2020. Looking closely we see that GFCF growth leading into 2022 was roughly three times final quarter growth. In other words the dawn may have plateaued.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Then there are a few downers. The Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) is a more rapid lead indicator based on monthly surveys measuring factors such as business activity, changes in sales, staff numbers, deliveries, purchases, and senior executives’ future expectations. The PMI went negative in February 2023.

To make matters worse, until this Sunday there had not been a day without rolling blackouts this year. The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) forecasts 0.3% productivity growth for 2023, while Treasury forecasts 0.9%, both dismal. SARB also indicates that private GFCF was already declining by Q2 last year, the latest period covered by its analysis. In these conditions, expecting a repeat of last year’s 4.7% growth is too optimistic.

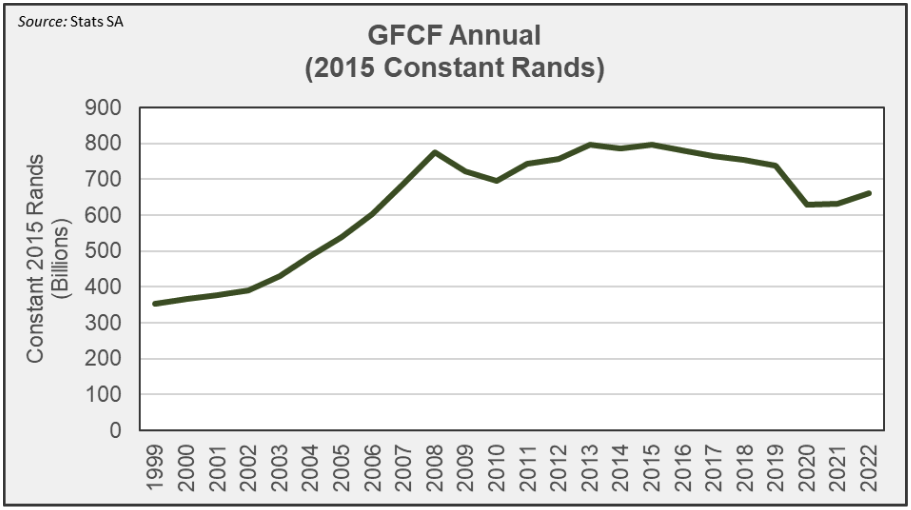

The bigger picture above makes matters even more interesting. To start with, we see what a real investment boom looks like. In 1999, there was about R350-billion of new investment per year, which more than doubled to R775-billion in 2008. (Note: these are “constant 2015 rands” taking inflation into account and are used throughout this analysis). In the boom, about three million jobs were added.

Then came Zuma and the Global Financial Crisis, shrinking investment by 10%. Then there was a “recovery” from 2010 to a new peak of almost R800-billion in 2015. Thereafter, came a slow, uninterrupted decline through President Cyril Ramaphosa’s ascendency before the sharp cut concurrent with the pandemic and lockdown. Finally, we see the little, partial uptick, which was the focus of the first graph.

The bigger picture

In the bigger picture, we see that GFCF is down 10% from 2019 and is 15.9% below the 2015 value. It is curious that the absolute investment peak was during Zuma’s reign, not Ramaphosa’s. Even at “new dawn” 4.7% growth, from here onwards it would still take until 2027 to return to Zuma’s peak GFCF level, and that is unrealistic.

For context, it is worth noting that peer markets including India, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Rwanda, Vietnam, Brazil and Turkey have already exceeded pre-pandemic GFCF levels.

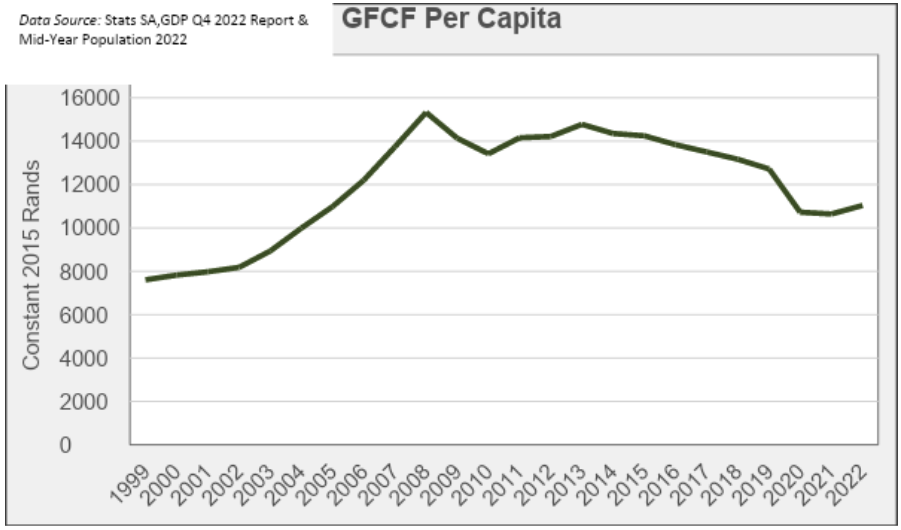

However, we advise a word of caution when looking at the graph above. South Africa’s growing population should mean increased production, but without added factories, offices and equipment, something else happens. So here is a graph showing real investment per person.

We think the picture above is simply devastating and should be more widely known. It shows that while absolute investment peaked in 2015, per person investment peaked before Zuma, back in 2008, at a little more than R15,000 per annum. One of us, Mlondi, was 10 years old, and the other, Gabriel, was 18 at the time. By 2019, new investment was down to about R12,500 per person. Last year it was only R11,036. We grew up in a shrinking world.

Zuma’s “recovery” – 2010 to 2013 – was a false dawn, ushering in endless shrinkage. And if that pattern repeats, investment will fall below R10,000 per person before the end of this decade. In the absence of policy change, we consider that inevitable. But even if we are wrong and GFCF grows at last year’s “new dawn” pace, it would still take until 2032 before the 2008 record of R15,320 investment per person is beaten. That would amount to 24 lost years of underinvestment.

Less capital

There is less capital to work with, so there are more jobless people. In 2008, unemployment hit a record low, at less than 22%; now it is above 32%. On the expanded definition, unemployment is 42%. In our age group, 25 to 34, it is 49.5%.

Our concern is that many analysts will overlook the hard data on real investments illustrated above and its connection to employment. This in turn means missing the systemic drivers of capital decline in South Africa.

After 2008, changes in the Presidency and Cabinet are not visible in the graph above, and we submit that is because GFCF doesn’t follow the wind or facial changes, it tracks policy.

Consider labour policy. South Africa has practically the world’s highest national minimum wage (NMW) relative to the median, meaning half all workers are technically outlawed. Local labour policy incentivises automation over hiring when it does not simply chase investment away to more liberal labour markets.

Then there is expropriation without compensation (EWC), which is in the policy pipeline via the Expropriation Bill, approved by the National Assembly. EWC is the opposite of GCFC.

Furthermore, the President continues to downplay intra-racial wealth inequality (which is odd given that he is a ranching billionaire) by doubling down on existing BEE. The Employment Equity Amendment Bill (EEB) awaits his signature, which would allow enforcement of Dis-Chem-style racial moratoria in the private sector. This alienates GFCF too.

Anti-capital policy is succeeding

These are three elements – labour, property, race – of the anti-capital policies that propel what the ANC calls National Democratic Revolution. Anti-capital policy is succeeding. There is less capital in South Africa. Unfortunately, that also means less work.

As a final twist, recall that annual GFCF per capita fell by 28%, from R15,320 to R11,036, between 2008 and 2022, but that is before depreciation. Take wear and tear into account and per capita annual investment had already dropped below R2,000 in 2019 and was projected to fall below R245 in 2022 because of overdue maintenance, based on the latest SARB data.

We know what good news looks like. The first graph at the top of this piece looked like good news because it showed more capital, not less. But add a proper timeframe and account for population and depreciation, and the picture looks alarmingly different.

EWC, EEB, and NMW should be replaced with policies that say: more capital welcome here.

Gabriel Crouse is the head of campaigns and Mlondi Mdluli is the campaigns manager at the South African Institute of Race Relations.